The Declaration of Independence and Fourth of July were the first American pop culture touchstones; plus a bonus podcast episode for the Fourth

The first Four Score and Seven Years of United States History saw the date and document it celebrates become the go-to for connectivity in American society

The Fourth of July was an arbitrary date to Americans until 1776 when the Second Continental Congress finalized its debates on the Lee Resolution and the document Thomas Jefferson was tasked with writing to support it. But by dating the Declaration of Independence “July 4th,” the founders invertedly laid the foundation for connection between Americans for years to come.

If the answer to the primary source analysis questions “Why was it made” or “What behaviors and ideas does it convey?” has something to do with the Fourth of July or the Declaration of Independence, then it supports my idea of the event as the original popular connection. The depictions and connections to the Fourth of July and the Declaration throughout America’s pop culture past are too numerous to mention, even in the first hundred years. But I suppose that is my argument; the early search for an American popular culture gravitated to July 4th and the Declaration the day celebrates because it was one of the few cultural pieces all Americans shared.

The person most responsible for placing in our minds an actual image of the Declaration of Independence having been forged and presented all on the Fourth of July is John Trumbull. The portrait painter is known and renowned for his early 19th century paintings depicting scenes from the Revolution, including a few versions of the same event, with the title of the most widely seen painting “The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776.” The reality is that the presentation by the committee of its document as shown took place in late June of that year, and the final signatures (Trumbull’s original painting is often referred to as “the signing” of the document) weren’t affixed until August. But the distribution and popularization of Trumbull’s work had its effect, even if it wasn’t desired by the artist, by putting the two together symbolically.

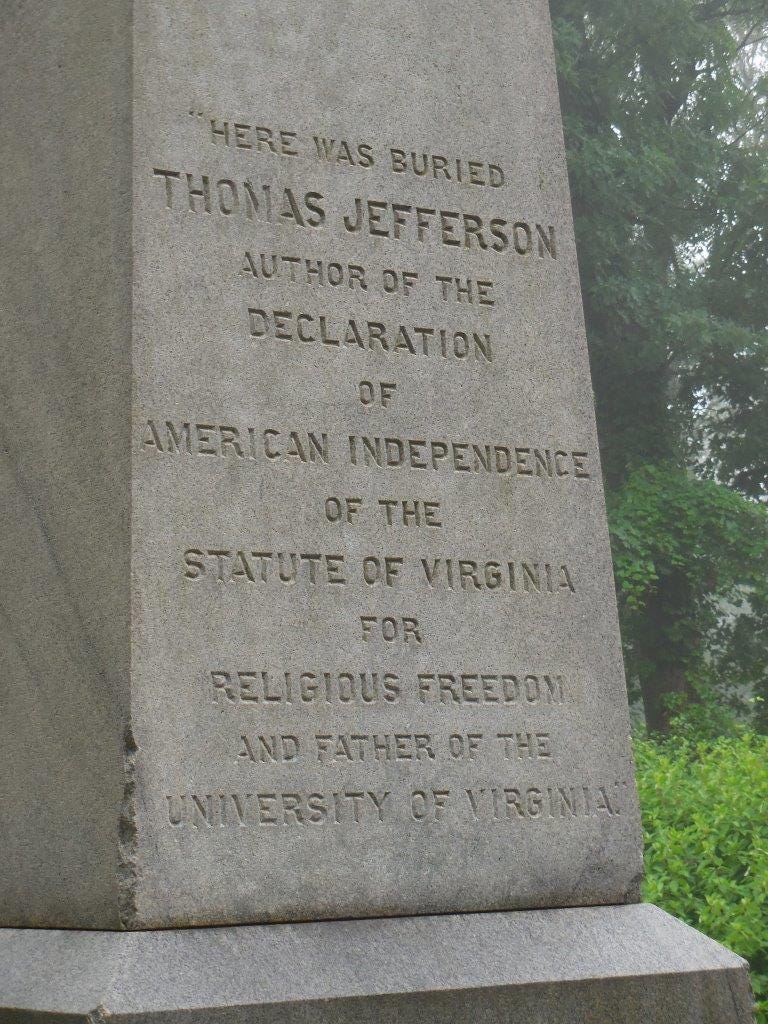

The Erie Canal was New York’s project, but had received the admiration of Declaration of Independence author, Thomas Jefferson himself, with plenty of correspondence between the former president and canal visionary, Governor DeWitt Clinton, as evidence. Beginning work on the project on Independence Day was symbolic of the United States gaining economic independence from the rest of the world because of New York’s “Grand Canal.”

Speaking of Jefferson letter-writing, in his later years he resumed communication with fellow revolutionary, turned political rival, then friend again John Adams. Adams co-wrote the Declaration and helped push it through the Congress. He also predicted in 1776 that the Fourth of July would be celebrated every subsequent year “with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other.” Both men died on the same day in 1826, on July 4th no less, the fiftieth anniversary of their Declaration of Independence. This coincidence was not overlooked by ordinary Americans then, and if anything, just further solidified the pop culture significance of the date.

The country’s First Women’s Rights Convention was held in Seneca Falls, New York in 1848. The entire region had developed, as predicted (or even greater than predicted) because of the Erie Canal. Elizabeth Cady Stanton was the principal author of that congress’s Declaration of Sentiments, which is nearly word-for-word the Declaration of Independence. This was done because nearly the entire population of America had recited the 1776 document as part of some version of schooling, making the new words placed that much more impactful. This could not have happened without a unified effort to develop an American identity, using the Fourth of July as its basis.

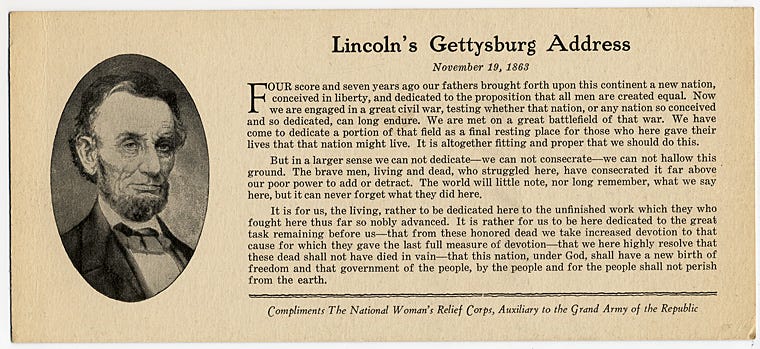

Following suit, Abraham Lincoln utilizes words and references from and to the Declaration of Independence in his Gettysburg Address to present his understanding of where the country had been, its current status, and his hope for the future as of 1863.

The famously short speech at the National Cemetery dedication ceremony could only be so concise with help from the popular culture of Americans in the 19th century.

The concerted effort to build a popular culture around Revolutionary War imagery, specifically the Declaration of Independence and the Fourth of July, in the first 93 years of the country’s history has resulted in another 161 years of regular references and uses. If there isn’t enough room in this post to address all of them from before the Civil War, there certainly isn’t enough space for all of them after it. Just the centennial and bicentennial themselves would present volumes of primary source materials.

Plenty of fellow historians and pop culture enthusiasts will point to a hundred years ago, the 1920s, as the birth of a true American Popular Culture. A wave of mass media which included radio, movies, literature, and special interest periodicals was cresting in that era, and Americans in nearly every setting were enjoying the same things all at once. Declaration of Independence and its holiday set the foundation for this 150 years earlier.

I exhibited "Your History Through Pop Culture” last year at the American Independence Museum in Exeter, NH during their Independence Day celebration, which arrives over a week after the 4th of July, to coincide with when the Declaration arrived in New Hampshire in 1776. Here are a pair of interviews with some of the youngest attendees that extends the ideas of the above essay:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Everything is a Primary Source to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.