Constitutional Convention Primary Sources for Constitution Day

The Constitutional Convention has been depicted in artwork many times over, with each painting representing the status of the country in the era

I am sorry if you’ve been aching for a EPS Substack post all summer, I have neglected my Substack in favor of other projects. It’s a good thing I teach Economics, otherwise I wouldn’t have the same awareness of opportunity cost! If you’d like to stay on top of Everything is a Primary Source I suggest you follow my Instagram or visit the website often.

Anyhow, today is Constitution Day, which recognizes the conclusion of the months-long Constitutional Convention in 1787, and the presentation of the original draft to the states for ratification. Unlike the Declaration of Independence, where there is only one or two recognizable artistic depictions, the proceedings of the Convention have been generated by painters regularly over the last 200 years or so. This could be because the meeting of delegates in Philadelphia was done in private, leaving what it looked like up to the interpretation and imagination of artists. Regardless, just like anything else manmade, each painting of the Convention is a representation not of conditions in 1787, but of the status of the country at the time the artwork was completed.

I’ve used this exhibit from Teaching American History many times in my teaching career, usually in Government or Civics classes. It is a collection of several US Constitution-themed paintings, starting in 1856 and ending with 1987, the document’s bicentennial. The activity could be something specific to Constitution Day (which makes this post a little too late…sorry) or when the class is studying the document and its living nature. There’s been few different arrangements to how students do their work, but essentially it comes down to comparing and contrasting the artwork, and analyzing each as primary source of their respective timer periods.

A teacher can assign one painting to a pair of students, or a pair to a single student, and then equip them with a Primary Source Analysis form.

For more details on how to lead your class and how to complete this form, see this section of the Classroom page over at everything-history.com . You can download a copy of this form and the other papers needed to teach the EPS way there, too.

In the “What does this tell you about ______________” section, student can write the year their painting was created, or some variation of the relationship between the people and the federal government or the state of the Union at the time.

The Teaching American History page has great contextualizing texts and other information about each painting. Some of the links are dead, unfortunately, but you can still locate the images in other places if you type in the titles and artists’ names.

Some sample outcomes or conclusions that come from the analysis include:

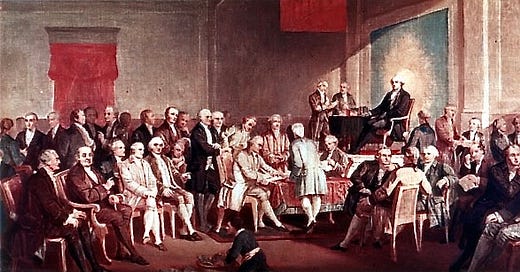

All eyes are on Washington, the man, in the 1856 painting Washington the Statesman by Junius Brutus Stearns, just as all eyes were on Washington, the city and seat of government in the tumultuous era of the Union in crisis.

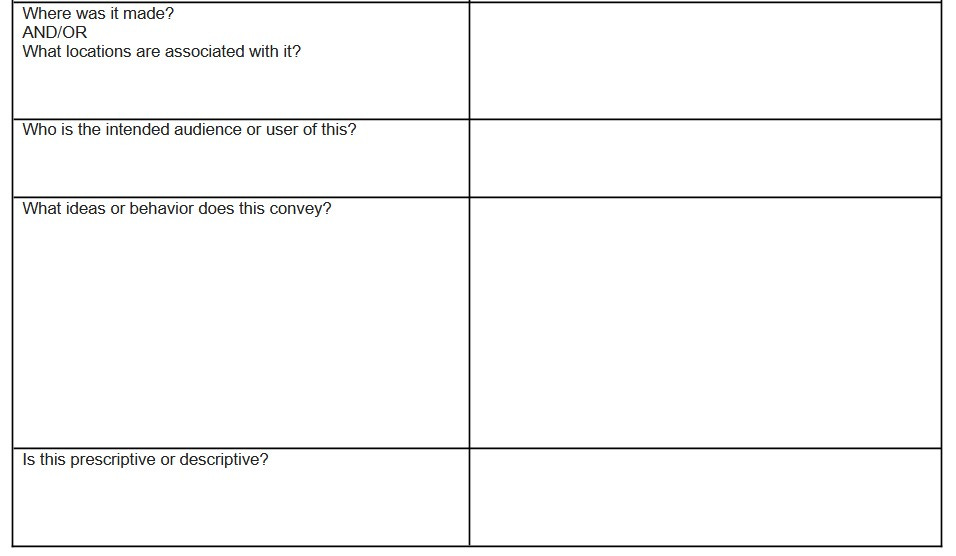

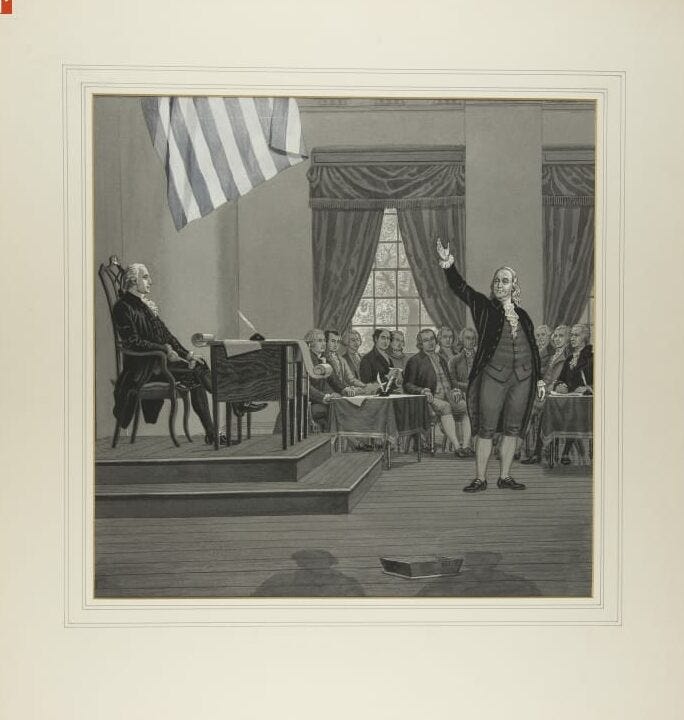

A very sprightly 81 year old Ben Franklin gives his famous “Rising Sun” speech at the convention’s closing in this Joseph Boggs Beale lithograph from the early 1900s. That era of innovation and industrialization, of which Franklin the inventor and scientist is the de facto patron saint, is shown here through a scene from 115 years earlier. It should be mentioned that this image is housed at the Henry Ford Museum of Innovation.

This very dreary depiction comes from the Great Depression era, when, just like the Civil War era, all eyes were on the Federal Government in Washington, hoping that New Deal programs would help fix conditions. Artist John H. Froehlich may not have been a fan as Washington looks overburdened and weak. This stands in stark contrast to the most recognizable Convention painting of them all, Howard Chandler Christy’s “Signing of the Constitution” which shows a strong, confident Washington, with what could only be described as an aura around him, from 1940.

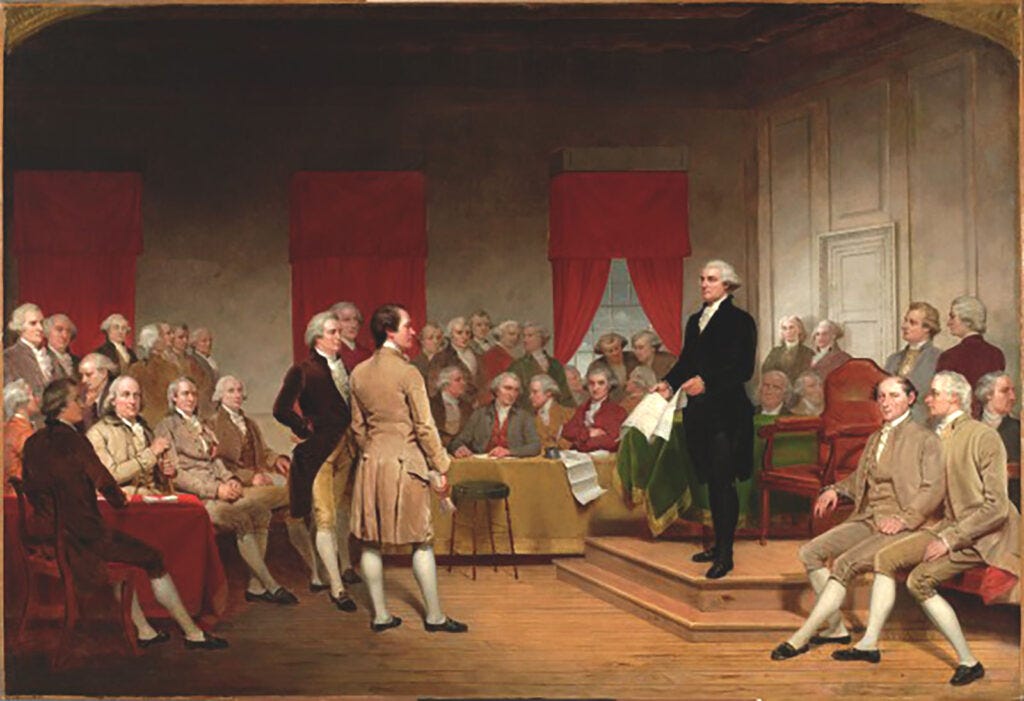

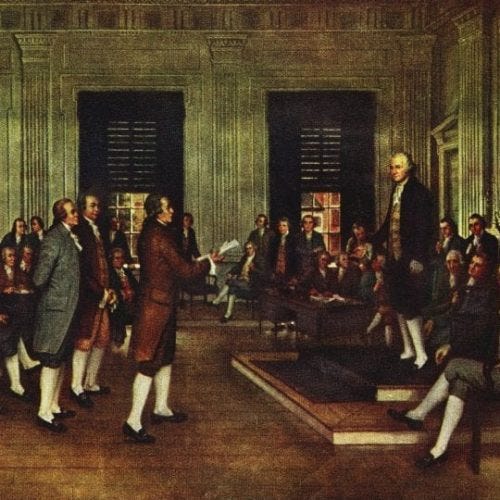

Finally, there is the 1987 work by Louis S. Glanzman, which is one of the few representations of the famous Independence Hall looking straight on to the president’s desk, instead of off to the side.

Coming out of an era of celebrating individualism and the power of the ordinary person, we get the perspective of being directly among famous names like Washington, Madison, Hamilton and Franklin as equals. Not to mention that remarkable feats and changes that had come about in the movies and TV, this painting is very representative of how Americans saw themselves in relation to America’s past.